Reviews

The New York Times, ARTS "Mordecai Shehori, an Israeli pianist who lives and teaches in New York, has built an enthusiastic following over the past 25 years, largely on the basis of a Romantic interpretive sensibility rooted in the early decades of the 20th century. Mr. Shehori himself is only in his late 50's, but his pianistic heroes are clearly from that receding time, and his preferred repertory, like theirs, takes in the virtuosic transcriptions of Liszt and others, as well as 19th- and early-20th-century works native to the keyboard. His approach is perfect for the music that interests him. And when his playing is at its best, as it was on Saturday, his readings are a fascinating reminder that the largely vanished performance style he has espoused took in not only bombastic, flashy playing, but also the gentlest and sweetest of pianissimos. Mr. Shehori offered some of each, with many gradations between. In the Bach Toccata in C (BWV 564), which he played in Busoni's arrangement, Mr. Shehori produced crystalline textures that kept the relationships between the music's contrapuntal strands completely clear, and he played the closing Fugue with considerable power. But the work's central Adagio section was the picture of gracefulness, restraint and precision. Debussy's "Valse Romantique" and Chopin's Scherzo No. 4 shared that quality, as well as a sense that Mr. Shehori had carefully considered the weight and place of every note within a phrase, and every phrase within the work. This concentrated interpretive style could have made Mr. Shehori's readings sound contrived, but he never crossed that line. And in more extroverted works — the Brahms Rhapsodie in E flat (Op. 119, No. 4), Liszt's arrangements of Schubert's "Soirées de Vienne, No. 6" and Gounod's "Faust Waltz," or a couple of period pieces by Vladimir Horowitz — there was a freewheeling quality that captured the sense of virtuosic improvisation inherent in the music." |

Cembal d'amour CD 111 |

| Cembal d'amour CD 122 Jascha Heifetz Live, Vol. 6 PROVOST: Intermezzo/ GODOWSKY: Valse/BENJAMIN: Jamaican Rhumba/KROLL: Banjo and Fiddle/BENNETT: Jim Jives/SCHUBERT: Impromptu; Ave Maria/BEETHOVEN: Cadenza and Rondo from Violin Concerto in D/BRUCH: Adagio and Finale from Concerto No. 1 in G Minor/DEBUSSY: La Chevelure; Girl With the Flaxen Hair; It Rains in My Heart/GRASSE: Waves at Play/SCHUMANN: The Prophet Bird/DVORAK: Humoresque/SARASATE: Zigeunerweisen Donald Vorhees conducts Bell Telephone Hour Orchestra/ Emanuel Bay, p. Cembal d’amour CD 122 66:10 (Distrib. Qualiton) Cembal d’amour producer Mordecai Shehori proudly boasts that his latest Heifetz installment now surpasses the number of private reissues of live Heifetz material, the DOREMI label having released only five volumes. This present survey covers ten years, 1942-1952, with Ronald Colman’s wartime introduction for Heifetz via Armed Forces Radio opening the program with the Intermezzo by Provost, a kind of Tristan clone with Emanuel Bay at the keyboard. Typical of the 1940’s acetates, some are in better condition than others, the orchestral tissue in the last movement of the Bruch Concerto (1947) being quite pallid. The 1942 Sarasate showpiece is distantly miked, but the playing, along with Dvorak Humoresque (1952) has the excitement we associate with John Garfield’s appearance in the movie Humoresque with Joan Crawford, the violin there courtesy of Isaac Stern. The wartime and Cold War sensibility produces some intriguing cuts for Heifetz, like the jingoistic Jim Jives of Bennett (1945) and Kroll’s popular Banjo and Fiddle (1947). The lightning speed of Heifetz at his prime is always a phenomenon to hear, particularly in the Sarasate and in the gymnastics of both Beethoven and Bruch. There is little of the intellectual about Heifetz’ approach: aside from the scholarship of the arrangements and the security of the playing the musicianship is geared to bravura or sentimental effects. The occasional heavy bow pressure, the sudden trnasposition to a higher register, all seem somewhat arbitrary and self-congratulatory. The sheer finesse and facility of the technique are ends in themselves. But every once in a while, a pearl of emotion shines through, and that is always worth the price of admission to a Heifetz recital. --Gary Lemco AUDAUD.COM |

Cembal d'amour CD/DVD 130 "Nadien, who plays in the Heifetz style, has a cult-like status among cognoscenti who savor marvelous fiddlers. " David Nadien (b. 1926) has by now gleaned a cult-like status among cognoscenti who savor marvelous fiddlers. A pupil of Betti, Galamian, and Adolf Busch, Nadien traces his personal development in his accompanying DVD interview with producer Mordecai Shehori at Nadien’s home. Appointed the New York Philharmonic’s concertmaster in 1966, Nadien managed any number of solo appearances and independent musical projects contemporary and pursuant to his orchestral duties. His tone and flashy technique often reminiscent of the Heifetz style--thinly piercing, razor-sharp, rhythmically driven--attest to a polished virtuoso who, like colleague Joseph Silverstein, nurtured a conductor’s “color” mentality while plying his particular instrument. The CD portion of this unusual set features four, standard bravura works which more than display Nadien’s especial command of his Guarneri del Gesu. The brisk gypsy-evocation Tzigane with Kostelanetz (11 February 1967) proves a spitfire rendition, sassy and inflamed at every bar. Like Heifetz, Nadien builds a colossal momentum against the orchestral play of strings, brass, and harp to elicit a resounding “Wow!” at the last note, the audience blistering its collective hands at this rousing performance. So, too, the GLAZOUNOV from Great Neck, Long Island (2965) under Sylvan Schulman moves with the same determined panache we hear from Milstein and Rabin from the same period of music-making. The rasping tone, the suave transitions, and the penchant for the long, arched line characterize all of Nadien’s musical concepts. The Great Neck GLAZOUNOV inscription suffers a bit of diminished sound quality after the presence of the Kostelanetz, but it still rings with authority. Considering that Leonard Bernstein never invited Jascha Heifetz to play with him and the New York Philharmonic--although Mitropoulos had--to hear Nadien in the Tchaikovsky Concerto is as close as we can get. The collaboration (8 October 1966) swirls with dizzying figures and huge rhetoric, the majesty of the piece never compromised by the swift tempos. The orchestral frenzy just before Nadien’s extended first movement cadenza proves hair-raising. The cadenza exploits Nadien’s suave, flexible flute-like tone long before the orchestral flute finally answers him. Nadien’s dynamic control must be heard to appreciate the expressive quality he can bring to a subito or graduated decrescendo. Bernstein catches fire in the final page of the first movement, and the house explodes in singed applause, not caring to wait a second longer. True to form, the Canzonetta wrings our hearts, only to lead us to the Cossack dance that spins on one foot in wicked circles atop a vodka-cluttered table. At times, whether Nadien used a violin or a thin rapier becomes a matter of debate. Some pitch dropouts and flutter bother an otherwise seamless rendition of this popular piece of musical fire-water. The exquisite exotique, Havanaise (1965), with Schulman sways and caresses the Cuban breezes with coy, sultry delight. Gorgeous sound, loving phraseology, and tropical heat permeate this veritable love-song/picture post-card of sand dunes and amorous assignations. The sound here is top-notch, the musical excellence again rivals our friend Heifetz. The 68-minute DVD is shot at Nadien’s home by Mordecai Shehori, and we can hear the occasional question put forth as Shehori stays invisible, behind his tripod. Nadien sits on his couch, relaxed: he will smoke two cigarettes in the course of the conversation. Rarely does the interview image break away, but we do see photos of David, his father, his teacher Betti, and musical influences, like Piatigorsky, Oistrakh, and Heifetz. Nadien’s father was a bantam-weight prizefighter--aka George Vanderbilt--who loved the fiddle. Enrolled at the Mannes School of Music in New York, David came to study with Adolfo Betti, lead violin of the Flonzaley String Quartet, who took David to Italy 1938-1939 and gave him pieces by Fritz Kreisler. “There was no ‘method’ as such, but Betti gave me direction.” When the war broke out, Nadien came home; he recalls sailing on the Normandie, and Shehori supplies a photo of the magnificent, doomed ship. We also see various programs of the period of Nadien’s development from Town Hall through Carnegie Hall. At the age of eighteen, Nadien was drafted into the US Army: he recounts the various stages which led to his assignment to the Armed Service Forces Orchestra. It was through the auspices of George Szell (a favorite collaborator) that Nadien won (1946) the coveted Leventritt Award and an appearance with the New York Philharmonic, the GLAZOUNOV Concerto with Szell. In 1966, Leonard Bernstein auditioned concertmasters after the departure of John Corigliano, and Nadien earned the post. Nadien recounts celebrities with whom he played: Oistrakh, who played Mozart and puzzled over the duration of a grace-note until Nadien suggested it serve as part of a 16th triplet; Menuhin, who inquired after Nadien’s high, elegant bow-arm, but which Nadien thought better than to have Menuhin adjust: “he was the mentor and idol of so many of us; I didn’t want to add to his already disturbed psyche about his execution.” Nadien remembers Toscanini with particular vigor: “he had a sensational stick-technique, totally informative, every cue alerted us to our task; he had good rhythm, which did not drag; he had good taste; he made us move together without becoming stiff.” Nadien concludes by expressing his concerns for the future of music, especially “live music.” He loathes what he calls “phoniness” and “manufactured music.” He picks up a violin, a 1980 replica of a Guarneri del Gesu, the “Lord Wilson,” and plays a bit from Kreisler’s Liebesleid. Nadien’s wife, Margo, joins the interview and expresses a few divergent opinions and memories, and she rolls her eyes when David claims she recalls incorrectly, like how many hours he practiced. Finally, Nadien huffs his impatience: “I’m getting hungry; let’s have lunch.”

|

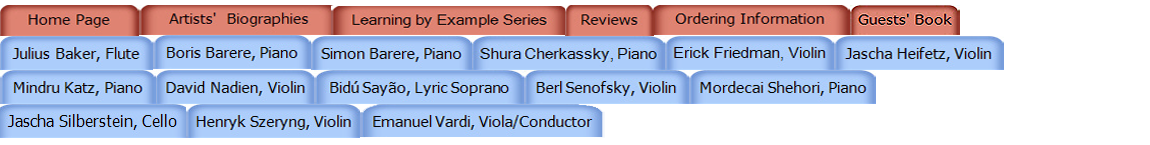

| Cembal d'amour Sitemap |